Behavioral analysis a key in solving violent crimes

The behavioral analysis process, once called profiling, can help investigators after all leads have been exhausted and the case is stalled.

Posted — UpdatedFrom January 1996 to February 1997, an unknown man was raping and killing women on the streets of Raleigh.

The pattern was lifeless bodies left out or “displayed” after being sexually assaulted and strangled. Many victims were found nude with only shoes and socks.

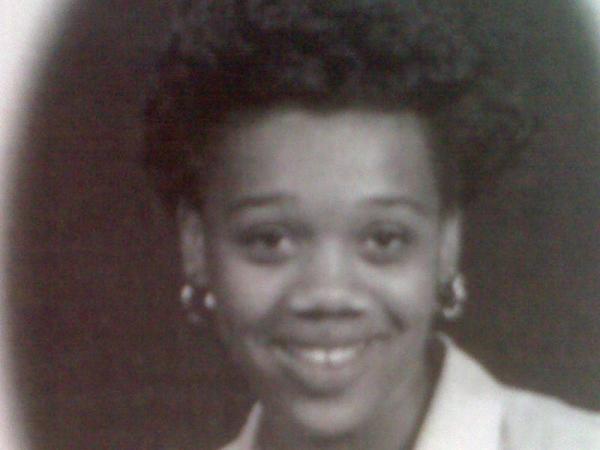

When investigators arrived at the first murder scene, where Patricia Ashe’s lifeless body was lying out in the open behind a building, they did not know it was the work of a serial killer.

As bodies of poor black women continued to turn up inside Raleigh’s Interstate 440 Beltline, however, authorities began to develop a profile for a nameless, faceless serial perpetrator.

To know their perpetrator, they had to know their victims.

"Most had a drug addiction problem. They were out on the streets," said Rick Poplin, a former Raleigh police detective who was the lead investigator on the case.”

“They didn’t expect he was a dangerous or evil person. He was able to exhibit one type of behavior, and then another type of behavior shortly after that,” said Raleigh police Sgt. Judy Sholar.

As many investigators do in serial cases, Poplin and Sholar began formulating an idea of the kind of person who would commit these crimes.

First, they studied the relationship between the offender and the victims. Then, they studied the victims.

They took their profile to the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit in Quantico, Va., where the case was given a fresh set of eyes and where analysts agreed that investigators were on the right track.

The behavioral analysis process, once called profiling, can help investigators after all leads have been exhausted and the case is stalled.

“It could be the study of an offender, a victimology of a victim, or a media strategy,” said FBI special agent Paul Minella, one of two field coordinator for the BAU.

The unit was recently called in to provide assistance in the investigation of six women whose bodies were found in a rural area of Edgecombe County over the past four years.

“I subscribe to the FBI approach,” said Jon Perry, a 41-year law enforcement veteran trained by the FBI in behavioral analysis who worked the high-profile BTK serial killer case in Kansas.

In that case, Dennis Rader sent letters describing the details of his killings to police and local media outlets from 1974 to 1991. He was arrested in 2005 and convicted of killing 10 people.

“What the bureau did was they identified 36 serial killers, interviewed them and came up with typologies,” Perry said. “

Gregg McCrary and John Douglas, the FBI agent immortalized by the 1991 film “The Silence of the Lambs” and author of the book “Mindhunters,” were pioneers in the behavioral science industry in the 1970s.

Eventually, the technique developed into an FBI unit devoted to the psychology and science of analyzing violent crimes.

“Psychopaths commit crime because, why not? They have no compunction against hurting others or killing others,” McCrary said. “They’ve done a lot of brain scans and their brains actually fire differently than the brains of non-psychopaths.”

In the mid-1990s Raleigh case, Sholar and Poplin’s instincts were correct.

They assigned undercover officers to keep surveillance of certain areas of downtown Raleigh.

John Williams was arrested during an attempted sexual assault in February 1997 and subsequently named a suspect in the Raleigh crimes.

He was a homeless drifter from Georgia who never stood out to investigators when they sought leads at homeless shelters throughout the city.

“Often times, the killer is the person in the community you don’t see," Perry said.

He was convicted in two murders and five rapes and is currently awaiting execution.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.