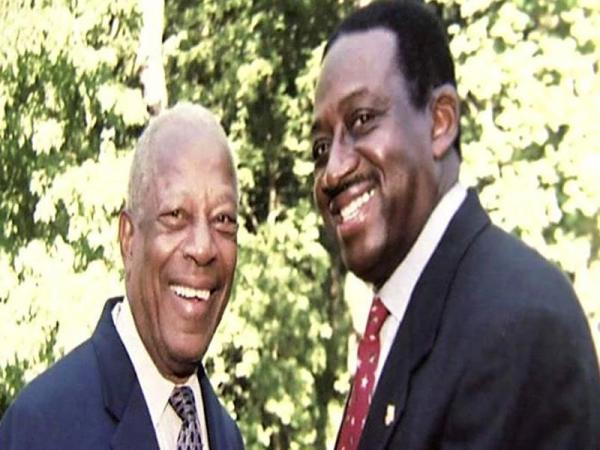

NCCU coach, US Olympic chief LeRoy Walker dies

LeRoy Walker, a legendary track coach at North Carolina Central University and the first black person to head the U.S. Olympic Committee, died Monday in Durham. He was 93.

Posted — UpdatedHe is survived by a son and a daughter. His wife, Katherine, died in 1978.

The Scarborough & Hargett Funeral Home in Durham is handling funeral arrangements for Walker, but no date has been set. A cause of death has not been determined.

George Williams, track and field coach at St. Augustine's College in Raleigh, said Walker was a mentor and friend.

"It was Dr. Walker who told me how to run a track program," Williams said. "Everything that I win is Dr. Walker."

Williams followed in Walker's footsteps as head coach of the U.S. Olympic team, but said he never stopped learning from the man who blazed that trail.

"I was not one of his athletes and he took me under. He believes in people," Williams said. "Dr. Walker is, in body, he's gone, but in knowledge and life, he's still alive and he will always be alive. He taught one to teach one, and that will go on forever and ever."

N.C. Central Chancellor Charlie Nelms called Walker "an accomplished figure in athletics and a treasured leader who will be greatly missed."

"He leaves a rich legacy that will continue to live on at NCCU," Nelms said.

Former WRAL News anchor Charlie Gaddy, who wrote a book about Walker in 1998, said Walker was the most remarkable person he ever met.

"(At the 1996 Olympics,) I was walking with him through the lobby of a big hotel there. It was amazing because people from Europe, Asia and South America, they all knew him," Gaddy said. "It was like walking around with a rock star."

During a coaching career that spanned four decades, Walker trained dozens of All-America athletes and national and international champions. He also worked his way up the ranks of the U.S. Olympic Committee and was at the helm of the U.S. team when the 1996 Summer Olympics were held in his hometown of Atlanta.

"A lot of young blacks, Hispanics and other minorities can see that, if you keep plugging away and pursuing excellence, something good can happen to you," he said in a 1992 interview. "I've always taught my teams success is a journey, not a destination. I think it's a good message to understand."

Walker's journey began in Atlanta, where he was the youngest of 13 children. Following the death of his father, he moved at age 9 to Harlem, N.Y., to live with an older brother. There, he helped with his brother's three restaurants and window-washing business to survive the Depression.

He attended Benedict College in Columbia, S.C., on a basketball scholarship – he also played football and was on the track team – and planned to pursue a career in medicine after graduating. However, because the only two medical schools that accepted blacks at the time had long waiting lists of applicants, he went to Columbia University and earned a master's degree in health and physical education.

Walker parlayed his degree into teaching and coaching positions at Benedict and Prairie View University in Texas before moving to Durham in 1945 and taking a job at N.C. Central. There, he built a reputation as a demanding, detail-oriented coach, training athletes like Lee Calhoun, who won the Olympic gold medal in the 110-meter hurdles in 1956 and 1960.

Overall, Walker inspired more than 100 All-Americans, 40 national champions and 12 Olympians in track and field. He also wrote three major books on physical education and track and field.

"What happened to my athletes is what I remember. Not only the all-Americans or the national champions or the Olympic medalists, I take pride in what all my athletes are doing now," he once said. "When I see them as doctors and lawyers and strong citizens in their community, I think that influence is what pleases me most."

He returned to school briefly in the late 1950s to pursue a doctoral degree and became the first black to earn a Ph.D. in biomechanics from New York University.

While working at N.C. Central, Walker also served as coach or adviser to track teams from Israel, Ethiopia, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and Kenya. In 1976, he was named head coach of the U.S. men's Olympic track-and-field team for the Summer Games in Montreal, becoming the first black to head a U.S. Olympic team in any sport.

The year after the Olympics, he was named to the U.S. Olympic Committee. He served on various committees and was chairing the development and grant-making committees by 1985. He was named the organization's treasurer in 1989 and was elected president in 1993.

"It's not wrong to be mentioned I would be the first black," he said shortly before taking over as president. "But (former British Prime Minister Winston) Churchill once said it's not enough to prepare yourself to do your best. You must prepare yourself to do what's required. I want people to know this can happen. On the other hand, if they look at my record, you wouldn't think I've achieved this because I am black."

During his tenure on the U.S. Olympic Committee, he also served as senior vice president for sport of the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games, which won out over sentimental favorite Athens, Greece, to host the 1996 Summer Games and mark the centennial of the modern-day Olympics.

"If I had to write the scenario for a movie, some people would not believe it," he said in a 1992 interview. "A guy born in Atlanta, where segregation was rampant, goes through all this, then returns for the centennial celebration of the Olympics as, 'the top person' of the national Olympic committee. It sounds Hollywoodish, yet there it is."

In 1983, he was inducted into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, and four years later, he was inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame for his contributions to the American Olympic movement.

"Throughout my service with the Olympic Committee, all I ever wanted to do was a good job," he once said. "Each time I was named to a new committee or a new post, I wasn't looking for anything beyond doing well the task at hand."

Walker moved from N.C. Central's track into its administrative offices in the late 1970s, serving as vice chancellor. He was named chancellor in 1983 and led the university for three years before retiring. As chancellor, he showed a knack for fundraising, including securing money for an athletic complex on campus, including a gymnasium that bears his name.

Even in retirement, he continued to teach young athletes and organize sporting events. He served as president of The Athletics Congress, the governing body for U.S. track and field, for four years, he brought many top track-and-field meets to Durham, and he was a key figure in putting together the 1987 Olympic Festival in North Carolina.

Walker also served one term as president of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics, which named its annual Champions of Character Award for sportsmanship in his honor.

“What a joy of effort there is in observing students – the gifted and not so gifted, the typical and atypical – discover that the most precious gift of all possessions is the power over themselves – the power to withstand trial, to bear suffering, to front danger," he once said.

• Credits

Copyright 2024 by Capitol Broadcasting Company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.